INFO

Nothing is gonna change my world, exhibition of Lucianella Cafagna and Claire Piredda

November 21st – December 1 2021

nothing’s gonna change my world unites the poetic worlds of Roman artist LUCIANELLA CAFAGNA and Italo-Canadian sculptor CLAIRE PIREDDA.

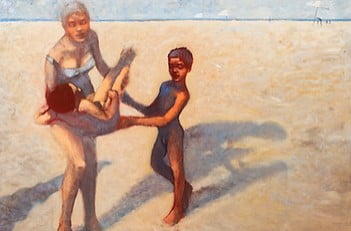

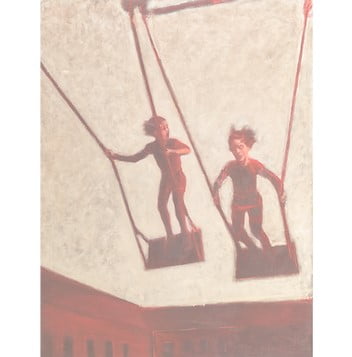

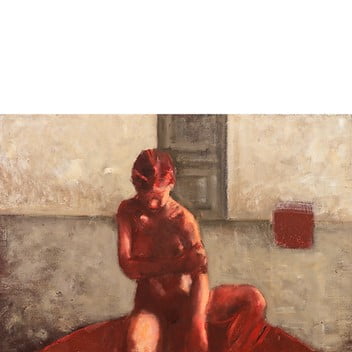

The work of the two artists is centered on the themes of childhood and early adolescence, explored by Cafagna on canvas and by Piredda through her terracotta heads and figures. In particular they are acute observers of that delicate spurt of growth which sees the child’s entry into early adulthood, and the layers of change involved in this rite of passage.

The exhibition title nothing’s gonna change my world – the iconic refrain from the Beatles’ Across the Universe – is perfect for the ‘significant moment’ that Cafagna and Piredda are concerned with. But their young creatures manage to express change without transition: they are at once figures of uncertainty, figures of joy, figures of conflict and figures of budding sensuality – caught between their new self-awareness and a sense of loss of their previous state.

They are precisely the pools of sorrow, waves of joy articulated in the lyrics of Across the Universe. The pathos and pains of growing up are before us, reminding us of that brief interlude when we are torn between the need to affirm our new existence and a brave, final bid to keep things as they are before ceding inevitably to the impact of a whirling, fast-changing world.

Lucianella Cafagna was born in Rome in 1968. She studied at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris and subsequently spent a period training in the studio of Pierre Carron, a protégé of Balthus. In 2011, Cafagna took part in the 54th Venice International Art Biennale with a life-size work exhibited in the Italian Pavilion, while in 2019, Rome’s prestigious museum Palazzo Merulana held a retrospective of her work.

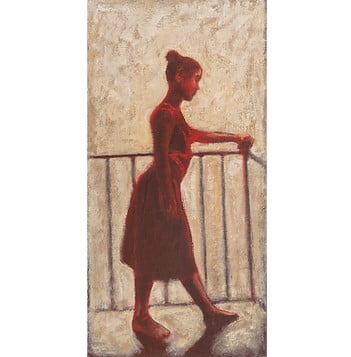

Childhood and adolescence are recurrent themes in Cafagna’s art, which blends the formal elegance of traditional training with a trajectory into the contemporary world. Art critics have highlighted her ability to evoke a sense of timeless suspension, her subjects hovering between memory and oblivion as poignant reminders of our evanescence.

Claire Piredda was born in Montreal, Canada in 1963. A versatile artist, she studied painting at the Rome Academy of Fine Arts and sculpture at the city’s Temple University Tyler School of Art while also attending the Costume & Fashion Academy.

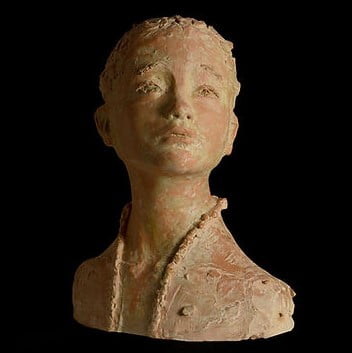

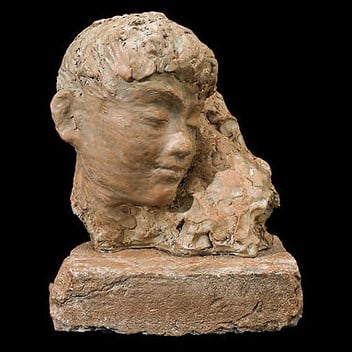

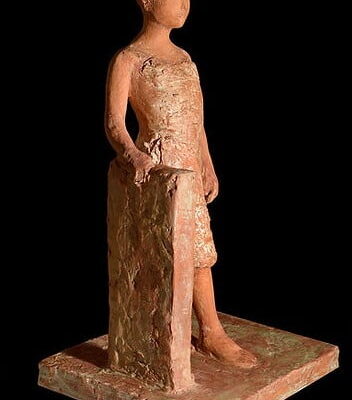

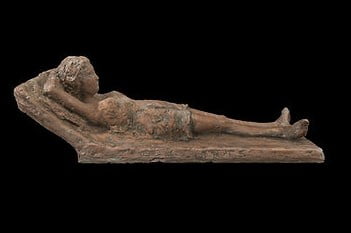

Piredda’s sculptures in unglazed terracotta of truncated busts and small-scale figures range in color from dull ocher to red. Harking back to the naturalism of the 18th-century French school of sculpture, Piredda exploits to the full the versatility of her material. With skill and delicacy, she pulls and pinches life from her raw clay, creating expressive, meditative works that remain hauntingly tender.

This long-anticipated exhibition has been specially chosen to mark the opening of the gallery’s new space at Via Giulia 13 and its change of name, passing from RvB Arts to Von Buren Contemporary.

WAITING AND MODESTY

Before approaching the works in Lucianella Cafagna’s new exhibition, I wanted to focus on one of her paintings that I am lucky enough to own. It is a portrait of the artist’s mother Aurora, whom I never met and of whom I know almost nothing. It is a painting dominated by the color blue, which highlights above all a deep and, dare I say, poignant love towards a very beautiful woman. Silent and at the same time powerful, the portrait conveys other sentiments too, sentiments which I have found in these new works: a longing for protection, which Lucianella seems both to request and to offer; a sense of disorientation in the face of the mystery conjured up by the passions; and a feeling of enchantment, which on the surface may seem to be loneliness, but in reality is the waiting for something that lends fulfillment to every decision and emotion. Lucianella does not give in to the temptation to provide answers, but instead asks herself questions, and these new paintings, in which blue often yields to the color of rust, testify to a line of exploration perpetually enlivened by these questions.

They are vibrant works in spite of their apparent immobility, and communicate the sense that the subjects portrayed are not engaged in something decisive and definitive but rather suspended in a moment in which the act of waiting takes on the dimensions of an epiphany or catharsis with respect to a fragile condition. It is from this suspension, both surprised and throbbing, that the longing for protection arises, while the combination of these opposing elements generates a hypnotizing and mysterious atmosphere, which extends to the artist herself. They are paintings that are at once rich in content and light in language, dense in elaboration and gentle in the result, because Lucianella has courageously chosen sincerity over virtuosity and intellectualism, and gestures, actions, often hesitations, are a prelude to something we can only imagine, sometimes hope for. And even when the atmosphere is tinged with melancholy, they continue to have the grace and warmth of the process of sharing.

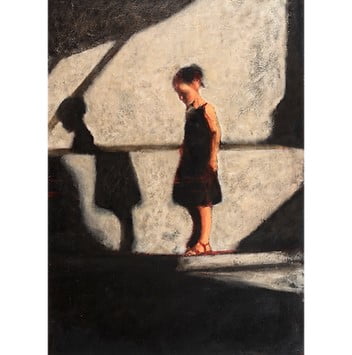

In my favorite painting, a little girl dressed in black with her eyes lowered to the ground is illuminated by a light coming from over her shoulders: the shadow is reflected on a wall with a step, but what interests Lucianella is not the geometric game of the refraction, albeit impeccably executed, but the emotions that the child is experiencing. Her expression is one of sadness but her features are blurred, and the result is a feeling of modesty and empathy: the pain can be relieved precisely because it is immortalized in a dimension of suspension, and the breath derives from the painting itself.

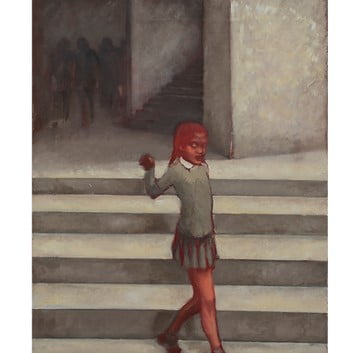

Another little girl, dressed in red, is walking down the stairs in a building shrouded in darkness. In this case, the sense of mystery is deepened by the place itself, but once again the cathartic dimension is of interest: the little one is portrayed in an area of light, the only one, and hers seems to be a choice regarding salvation. She too has a bowed head and a melancholy stance, but it seems that it is something that belongs to the past, because she has chosen the right path. The composition is exquisite and the stairs are created with skill but the punctum, to quote Barthes, is once again in her blurred features, which allow us to pick out her passage towards the light.

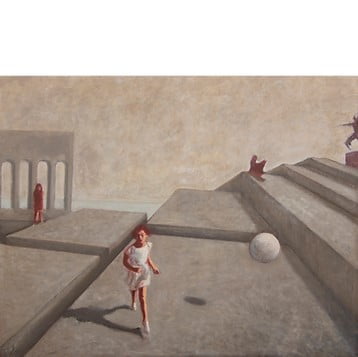

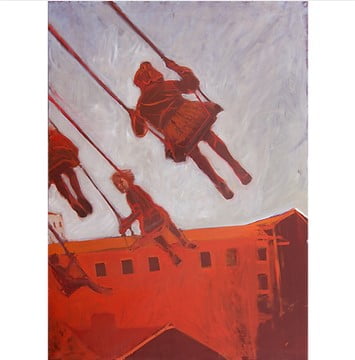

A third child, depicted on a swing, turns her head to look at her friend sitting behind her: the way in which her euphoric expression is captured is admirable but this time the mystery is entrusted to the response of her companion, portrayed from behind. Is she smiling too? Is she afraid? Is she bored? One has the feeling that the artist identifies herself above all with this other little girl and embraces the mystery of her reaction, while the child stands out against a blue sky overlooking a building darkened by a prematurely set sun. Around them, the other figures are only shadows or incomplete bodies. In these paintings, the spaces are wide and deserted but once again, what seems to dominate is not the loneliness of the portrayed characters, but the affirmation of personalities, even very young ones, who manifest dignity precisely because they are aware of their fragility: a little girl dressed in white chases a ball suspended in the air in an open and enigmatic space, consisting of a flight of steps and huge concrete blocks. The biggest mystery, however, is represented by the ball, which seems to be waiting for the child to arrive: once again we are back to waiting.

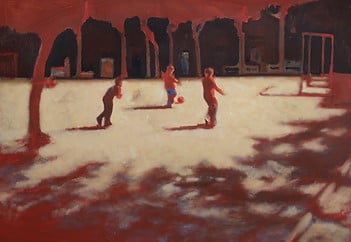

No less mysterious is the dark space that in another painting surrounds the field where a group of children are playing football: it almost seems to be a gloomy forest bordering a place of light, but in the darkness the doors and entrances of the surrounding buildings stand out.

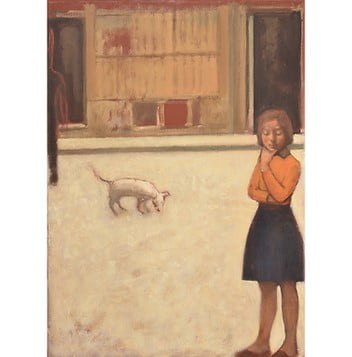

Along this pictorial path marked by expectation and enchantment, it is the mystery created by the children’s expressions that seems to fascinate Lucianella. Another little girl has a pensive look and leans her chin on her hand. Behind her a dog is shown, in a timeless space: it is the little girl who appears to be studying us and the artist herself, more than we are studying her. This ambiguity sometimes lends a sense of impudence to fragility, as in the case of a girl dressed in green who is coming down the stairs, or it mixes fragility with modesty in the image of another girl, naked, who is about to dive into the water: yet another moment of waiting, epiphany and catharsis.

The deep and touching charm of these paintings, which are candid to the point of laceration, is in the suggested, the unspoken, sometimes in the hidden, while the completeness of these graceful works finds its harmony primarily in a sense of modesty.

Only now do I understand why the painting I have at home has always moved me: her mother Aurora had beautiful blue eyes, but Lucianella preferred to portray her with her eyes closed and the hint of a smile.

ANTONIO MONDA

LET’S PLAY A GAME

The first time I saw Claire Piredda’s little heads, I imagined her softly blowing on them once she had finished shaping tufts of hair, buns, eyes, noses, ears and thin necks with her fingers. It was only via such an act of magic that I could explain so much life in these children’s faces.

On the other hand, Claire retains, hidden in the crease of her shy smile, a tiny but indelible trace of childhood. So, she knows. It is evident that she still clearly remembers what it is like to be in that moment when childhood is about to end and we understand that yes, we are growing up, but for now it is better to go and play, or remain absorbed, leaning on a low wall because it is still too soon to propel oneself into the future.

It is that particular moment when you know that life is waiting for you and you look at it from afar, to understand what promises it is making to you, and every time you bite into a piece, it is an adventure. It is the moment before you are asked to really think it through though. That is why it is an enchanted moment.

And only thanks to a magic spell can a substance retain the precise expression of that age which is little more than a flash.

In the eyes of Claire’s children, there is the pure poetry of those who can still see the essence of things. And since life is no laughing matter, here we are faced with very serious faces, because at that age everything must be taken seriously, given that growing up is a very difficult job and while every minute of the present is important, playing a game of Ring Around the Rosie is no less so.

It brings to mind Italo Calvino’s Il sentiero dei nidi di ragno (The Path to the Nest of Spiders) and Pin’s anger as he triumphantly brings the pistol that the group of men at the bar have asked him to steal only to find himself treated with indifference. “Grown-ups are an untrustworthy, treacherous lot, they don’t take their games in the serious wholehearted way children do, and yet they too have their own games, one more serious than the other, one game inside another, so that it’s impossible to discover what the real one is”.

Perhaps that is why, looking into these eyes of clay, I almost have the impression that they see things about us that we can no longer see, and that they are even able to make us a little uncomfortable because it seems they know about our sad condition as adults and pity our now poor ability to distinguish and understand the essential.

But while in these little heads, the exciting idea of being about to become a round and complex person is already resounding, there isn’t yet any trace of disenchantment, or the terrible temptation to judge others in order to define oneself. So we can contemplate their grace fearlessly and with admiration as they face that frontier, each in his or her own way. Just observe and listen: you can hear small hints of rebellion or glimpse a tiny surge of anger. One minute the electric expectation of something extraordinary is palpable, the next the hurt caused by an insult, or the pondering of a tangled thought, or even the indolence of those who prefer to cling to the child who almost is no more, while knowing that it cannot last long.

Sometimes you can also see us wince with worry or disappointment, like the intuition that one day, looking back on that very short period of time, they will feel an excruciating nostalgia.

VALENTINA ORENGO